Blogs

Living with Caterpillars: Experimentations Beyond Human-Centric Practices in Early Childhood Education – Part 1

With support from ECPN leadership team – Meagan Montpetit & Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw

This is the first blog post in a two-part series that addresses the ethics and politics of welcoming more-than-humans into early years classrooms.

This series invites you to walk alongside us – a group of dedicated educators, inquisitive toddlers, and me, an Early Childhood Pedagogy Network (ECPN) pedagogist – as we work to transform our ways of living and learning with caterpillars and other creatures that inhabit our early childhood centre in Kamloops, BC, within Secwepemcul’ecw.

As a pedagogist who thinks with common worlds[1], I experiment alongside educators with how our daily curriculum-making practices with children might centre ethical ways of being with each other and with more-than-human others during converging climate crises. I am interested in questioning the common early childhood education practices that shape the ways educators and children think and speak about animals and plants, in an effort to emphasize human/more-than-human interdependence.

The team of three educators and I had been working together for almost three years in April 2024 when we began to anticipate the arrival of caterpillars in the classroom. Like many early childhood educators across Canada, the team at this centre eagerly await the arrival of spring when the centre purchases caterpillars so children can observe them as they undergo their fascinating transformation into butterflies. Every year, this event becomes a key moment of inquiry in the toddler classroom.

As part of our work together, the educators and I had been establishing collective pedagogical commitments in response to a fundamental question: How might we respond to the inconsistent and unequal conditions of life in the 21st century, especially as they are emphasized by human relationships with land? How is the world in which these children are growing up shaped by humancentric logics that artificially separate human beings from other animals and plants? And, what kind of future might these children inherit, amid climate emergencies, economic instability and the disruptions these overlapping conditions cause to both human and nonhuman lives? With these questions and concerns in mind, we chose to orient ourselves differently to this year’s inquiry with caterpillars than had been done in previous years. We wondered if, by emphasizing collective noticing of other-than-human lives and intentionally nourishing slow, mindful rhythms, we could better respond to the challenges of a world where inequality and inconsistency are pervasive – not only among humans but across all forms of life.

In these blog posts, I recall many pivotal moments that shaped our experimentations from May through August, trying to connect with caterpillars as more than just “objects of study.” This shift toward a common worlds framework invited us to consider human beings as entangled within a broader “web of relations.”[2] I share these shifts through several small moments from everyday life in the toddler classroom because, as Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reminds us, how we move through the world creates the worlds we live in.[3] Simpson writes, “if we want to create a different future, we need to live a different present, so that present can fully marinate, influence, and create different futurities.”[4] For us, living differently in the present required several small, intentional shifts to engage with caterpillars and one another. We experimented with slowing down to notice body movements, tuning into caterpillars, emphasizing more-than-verbal ideas through drawing, and returning to our collective drawings to extend children’s ideas. With these intentional pedagogical moves, we worked to create conditions to nourish connection and complexity.

Reimagining our relationship with the caterpillars

(Note: All of the children’s and educators’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.)

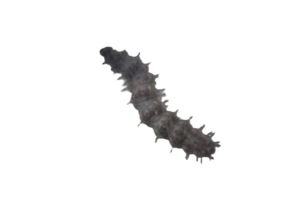

It’s the end of May and the director of the early years centre has just picked up a cardboard box containing the painted lady butterflies they ordered from a local toy and game supply store. Each classroom receives a small plastic container with tiny holes poked in the lid. It’s filled with caterpillars – some only a few millimetres long – crawling up the sides of the clear container and overtop of each other. Mashed-up food and feces cover the bottom of the container, which is quite different from the leaves and twigs found in the butterflies’ natural habitat. Our butterfly kit includes instructions for how to raise these caterpillars for the next few weeks, as well as activities aimed at instructing young children.

Preparing pedagogically

In the weeks leading up to the caterpillars’ arrival, we – educators and pedagogist – gathered regularly as a small team to discuss how we might welcome these more-than-human others in ways that would align with our ongoing pedagogical questioning. What might it require of us to meet caterpillars as neighbours? This question emerged from our pedagogical commitments, a specific set of concerns and hopes that we have created together to ground our actions and pedagogical choices in the classroom.[5] Over the three years we have worked together, we have aimed to understand what we collectively care about as early childhood education professionals. Through many conversations and multiple inquiries alongside children, we have developed a core set of educational desires: we want to create classroom conditions that invite slow, intentional rhythms, ones that nourish a pace of lingering and noticing together and prioritize space and time for toddlers and educators to engage meaningfully with each other – and, in this inquiry, with our caterpillar guests. Following the Common Worlds Research Collective[6], our aim with these slow tempos is to create conditions to collectively and carefully tune into the world and to amplify our relations with each other and with the more-than-human others we share this place with.

Importantly, we activate these commitments in our everyday work alongside children. As we plan how to engage with children and caterpillars with our pedagogical commitments in mind, we are obligated to reflect deeply on the activities that typically mark this time of year. Usually, planning for caterpillar experiences centres heavily on teacher-guided inquiry and human-centred modes of living. The focus is on teaching children facts about caterpillars – their life cycle, what they eat, where they live – using books and other learning materials. In this way, children are schooled in the miracle of metamorphosis through the Euro-Western scientific method of objective observation. These fact-based activities are supplemented with familiar songs and stories, such as Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. With all of these materials, the predictable path from caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly is depicted as well known, reinforcing a vision of the more-than-human as something to be observed and understood through familiar scientific techniques. In this approach, caterpillars are reduced to singular truths that humans can uncover and reveal.

As the educators and I discussed these common practices, we questioned whether this emphasis on scientific method was aligned with our desire to connect with the caterpillars – to slow down, linger and engage meaningfully with more-than-human beings. Instead, objective observation seemed to reinforce a humancentric relationship with the natural world in which we valued caterpillars primarily for what they could teach children about lifecycles. By introducing caterpillars within the unnatural confines of a plastic container, were we reducing these living creatures to objects of study, measuring their transformation against human-defined metrics of facts about their life cycle and eating habits? We wondered: What message does the traditional way of engaging with caterpillars convey? Who is active in this relationship? And, what kinds of knowledge matter? We acknowledged that this approach might subtly reinforce what Land et al. describe as the “narcissistic delusion”[7] that humans own the world and can manipulate land, animals and plants with impunity as long as the action serves human interests.

Because the educators and I work pedagogically, we asked ourselves: What kind of human/more-than-human relations does relating to caterpillars in this scientific way produce? Is this the kind of relationship we want to nurture in ourselves and the children? And if not, what kind of pedagogical processes might we create to help us slow down and tune into our interconnectedness with the world?

As we prepared to welcome caterpillars into the classroom, this collective thinking about how we might nourish a more attuned and reciprocal relationship with these caterpillars – and, by extension, with the broader more-than-human world – was crucial to how we constructed the inquiry alongside the children. Rather than treating caterpillars as mere objects of scientific study, we worked to craft pedagogical processes that might help us to see caterpillars as fellow beings with their own rhythms, needs and life cycles that are just as important as ours. In doing so, we hoped to foster a space where the children could not only learn about the world around them but also understand their role within it – a role that is interconnected with, rather than dominant over, the creatures with whom they share the world.

For example, when we wrote a letter to families and colleagues outlining our desires and intentions, many responded by suggesting that, as teachers, our role was to teach children the facts about life cycles. Their questions made us doubt our approach, prompting us to revisit our pedagogical commitments. It was through this ongoing return to our commitments that we found the resolve to continue our experimentation. We reminded ourselves that pedagogical work is inherently risky and often messy, precisely because it offers no guarantees of a predetermined outcome.[8]

After the caterpillars arrive at the centre, our first task is to transfer them from the small plastic tub to a larger enclosure. Usually, the educators efficiently move the caterpillars into the display case during naptime. In this way, the children meet the caterpillars for the first time through a plastic sheet – they are easily observable, but no one can get too close. With our commitment to slowing down and embracing complexity and connection, we decide to involve the children in the potentially dangerous transfer process.

After naptime, an educator and I invite a few children to gather at a low table to meet the new guests in our classroom. Together, we peer into the clear container, observing the caterpillars in silence before I slowly remove the lid. After a moment, I begin transferring the caterpillars one by one onto a paintbrush and into the larger enclosure. The children immediately respond.

“I don’t think he likes it,” says Spencer to the gathered group of children and adults. Speaking quietly to the caterpillar, he urges, “Go over there, friend.”

“Oh! He’s moving!” says Marla. “He’s so tiny! I see a daddy one.”

One caterpillar crawls along the length of the paintbrush as it is moved carefully through the air, carrying the tiny caterpillar toward its new home.

“He’s walking,” says Spencer.

Spencer’s eyes follow the caterpillar’s inching steps. He gasps as the caterpillar suddenly falls from the paintbrush into the new enclosure. “He jumped! He said ‘Wheeee!”

With Spencer’s comment, our collective attention turns toward caterpillar movement.

Later, once the caterpillars are all in the larger enclosure, an educator places their plastic home on the special table the group prepared before their arrival. Before the caterpillars arrived, the children and educators had spent a few days gathering sticks, leaves, nettles and other materials during their walks to a nearby park. They covered the table with a floral tablecloth and made a “welcome” sign in anticipation of the caterpillars’ arrival.

Peering over the edge of the table at the guests, Annabelle says, “They’re resting.”

“Hi Baby Bug,” says Frances.

“Ba! Baaa! Hi Ba!” says Molly, standing up on her tippy-toes.

The caterpillars move around the enclosure. They hang down from the roof, crawl vertically on sticks and leaves, and step over each other to get to the central food dish.

They are making us think about movement.

Marla drops to her stomach and slides along the floor, wiggling like a caterpillar.

Marla drops to her stomach and slides along the floor, wiggling like a caterpillar.

Harriet follows suit on her belly, bending her knees at a right angle and wiggling her whole body.

Spencer climbs to the top of the classroom slide and slides down headfirst with knees bent and both legs up behind him. He rushes around to do it again, this time hopping down the slide on all fours “like a caterpillar.”

Watching her friends, Priya declares: “I can walk like a caterpillar.” On hands and knees, she wriggles her body as she moves across the floor.

Others join in and soon the floor is filled with wiggling, rolling, twisting, squirming caterpillar-children.

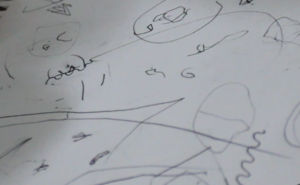

To slow down and linger with caterpillar-child movements, I bring my sketchbook and pens to the floor between the caterpillar table and the space where the caterpillar-children are moving.

“I’m going to draw how Marla, Harriet and Spencer are moving,” I announce to the small group of children in front of me. “I’m going to draw their caterpillar movements.”

Annabelle sits beside me and chooses a pen from the cup I’ve placed on the floor beside the sketchbook. She draws a long line across the page.

Priya comes over to look at Annabelle’s line. Taking a pen, she draws a curvy line. “Like this.”

“I’ll draw you while you walk like a caterpillar,” I say to Priya.

Taking my invitation, Priya repeats the same wriggling movement she made earlier and comes back to the paper to check my drawing.

“This is what I drew,” I tell her. “What do you think?”

“No, not like that,” she declares, taking the pen from my hand and marking a small circle on the page. “Like this.”

“Oh, I see,” I reply, studying her drawing and tracing the zig-zag lines with my finger. “Your caterpillar goes walking, walking, walking, walking.”

“My caterpillar goes walking, walking, walking, walking, like this!” says Harriet, drawing a curving line around the page.

Soon other children join us, alternating between embodying caterpillar movements, checking on the caterpillars in their enclosure, and drawing distinct lines on the page.

Thinking together, with drawing

At our meeting a few days later, the educators and I studied the photos, videos and drawings from this encounter. It seemed like the children were connecting with caterpillars by embodying their movements. We wondered if drawing together with children and caterpillars might help us to “become increasingly more sensitive”[9] to the multiple ways children show and share what they know, think and wonder. With artist and atelierista Sylvia Kind, we see drawing as a way to open space for speculating with children beyond words. Drawing is both a reason for coming together and a process for putting our ideas into conversation with others. Kind says that “drawings temporarily stabilize the elusive and give shape to ideas in their formation. . . . [Drawings] leave a trace of thinking.”[10]

The educators and I decided to use drawing practices to keep our commitment to creating processes for lingering with children’s ideas and connecting with caterpillars beyond just facts. Drawing helped us focus on caterpillar-child movements and bodies in the moment and keep those movements alive and present through our ongoing engagement with the drawings themselves.

To do this, we created intentional daily processes. First, educators brought the group’s attention to the caterpillars a few times each day. They sat down to watch the caterpillars alongside the children and write down what the children were noticing about caterpillars, with a focus on movement. Second, when I visited the centre, I created a specific time for collective drawing when both children and adults focused on caterpillars and movement with drawing. Third, we kept the drawings in the classroom as a living reminder of what the BC Early Learning Framework[11] calls our collective processes. The drawings became important traces of our thinking. We activated these traces by regularly revisiting the drawings, often at snack or lunchtime. As we looked at, added to and changed the drawings, they sparked further conversation and bodily experimentation: children moved like caterpillars around the room, consulted the drawings and moved again. In this way, the traces became part of our collective pedagogical decision-making processes.

Intentional practices toward envisioning alternative futures

Creating these intentional practices, which invited us to slow down and attune to the lives and worlds of caterpillars, encouraged us to consider the dispositions we hoped to cultivate in ourselves and the children who are inheriting an uncertain future. This is especially relevant in 21st-century British Columbia, where the impacts of climate crisis, driven by human activity, are becoming increasingly evident.[12] How might envisioning and inventing alternative ways of being with caterpillars nourish what author and activist Adrienne Maree Brown calls “visionary” dispositions for a world where “the changes are frightening and incomprehensible”[13]?

Brown suggests that cultivating visionary dispositions requires a shift from what she calls “competitive ideation” – where the focus is on finding the best idea from individual contributors – toward “collective ideation.” In this approach, the emphasis is on developing ideas that emerge from and benefit the whole group, which in this case included the caterpillar guests. In early childhood education, competitive ideation often appears as a practice where each child shares their individual idea, which the educator then records as part of a list. This approach contrasts with a more collective model where the process extends beyond individual contributions to include collaboration – refining and expanding on each other’s ideas. In this way, ideas build and evolve through shared influence, fostering creativity and collective meaning making.

The challenge and messiness of collective ideation resonates deeply in this inquiry because we work with toddlers who communicate more-than-verbally. We wonder if drawing might help us tune into the many ways these young children express their thoughts, ideas and relational understandings through their bodies, actions and other forms of expression. Intentionally remaining open to emerging relational knowledge-sharing practices (such as the drawing and movement practices we’ve created) brings us back to our commitment to foreground relational knowledges, sidestepping the usual focus on objective scientific observation of knowable life cycles.

With this way of working, it’s hard to know if we’re “getting it right,” but we are pulled along by our pedagogical commitments and the everyday excitement of envisioning unfamiliar knowledges through moving, mark making and collective embodied noticing.

In the next blog post, I will explore how the pedagogical practices we created reflect a broader effort to challenge human-centred approaches shaped by developmental psychology. By tracing the ways we experimented with alternative engagements, I will consider how these practices disrupt dominant narratives and open possibilities for more relational, multispecies ways of learning and being.

[1] Common Worlds Research Collective. https://www.commonworlds.net/

[2] Taylor, A. (2011). Reconceptualizing the nature of childhood. Childhood, 18(4), 420–433.

[3] Simpson, L. B. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

[4] Simpson, As we have always done, p. 20.

[5] Smith, T., Hann, C., Jeong, M., Montpetit, M., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2024), Catalogue of wanderings: Glossary and references. Early Childhood Pedagogy Network.

[6] Common Worlds Research Collective. https://www.commonworlds.net/

[7] Land, N., Vintimilla, C. D., Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., & Angus, L. (2022). Propositions toward educating pedagogists: Decentering the child. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 23(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120953522

[8] Land, N., Vintimilla, C. D., Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., & Angus, L. (2022). Propositions toward educating pedagogists: Decentering the child. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 23(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120953522

[9] Kind, S., & Po, J. (2024). Formations, re-formations and malleabilities: Working with children’s ideas. ECPN Conversation Series, June 17, 2024.

[10] Kind & Po, Formations.

[11] Government of British Columbia. (2023). British Columbia early learning framework, p. 5. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

[12] Kirchmeier‐Young, M. C., Gillett, N. P., Zwiers, F. W., Cannon, A. J., & Anslow, F. S. (2019). Attribution of the influence of human‐induced climate change on an extreme fire season. Earth’s Future, 7(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018ef001050; Montpetit, M. (2023). Reimagining climate relations with feminist earth-based spirituality through common worlds ethnography with young children [Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Ontario]. Western Libraries. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/9115/

[13] Brown, A-M. (2017). Emergent strategy: Shaping change, changing worlds. AK Press.