Slow Encounters with Orange Peels

- Home

- Field Notes

- Slow Encounters with Orange Peels

With support from ECPN leadership team Meagan Montpetit and Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw

Educators: Lori, Lily, Aya, Sandra, Christina, Mara

Children: Alex, Ayla, Caia, Eleanor, Holly, James, Lennon, Mika, Miya

While only a few glimpses of encounters are documented in this field note, the orange peels invited all children and educators at the centre, not just the ones named, to come and go, engaging in ways that extend beyond what is documented here.

Pedagogical Orientation

As a pedagogist, I am committed to creating early childhood spaces where knowledge is composed through relationships—with children, educators, materials, place, and more-than-human life. I work to cultivate conditions that honour the complexity and unpredictability of meaning making, where ideas take shape through dialogue, shared encounters, and collective experimentation. These are spaces that disrupt individualist logics and foreground the collective, spaces where new ways of being and thinking are composed within dynamic and situated relations.

In this field note, these commitments come alive with encounters with orange peels, remnants of everyday life that are typically dismissed. The orange peels’ stickiness, scent, and slow decomposition invited us to stay with the overlooked, to think with waste as something alive, and to consider how relations might form around what is usually cast aside.

Meeting Orange Peels (Differently)

On the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations, a group of children and educators gather in an early childhood space to think slowly and carefully with something rarely considered a classroom material—orange peels. Often discarded without a second thought, orange peels call us into their presence, not as passive remnants, but as active participants in our inquiry. They stain, resist, crumble, and refuse. They mark the table, our hands, and our collective thinking. They interrupt what we, the humans, think we know about food waste and invite us to reimagine what matters in early childhood education.

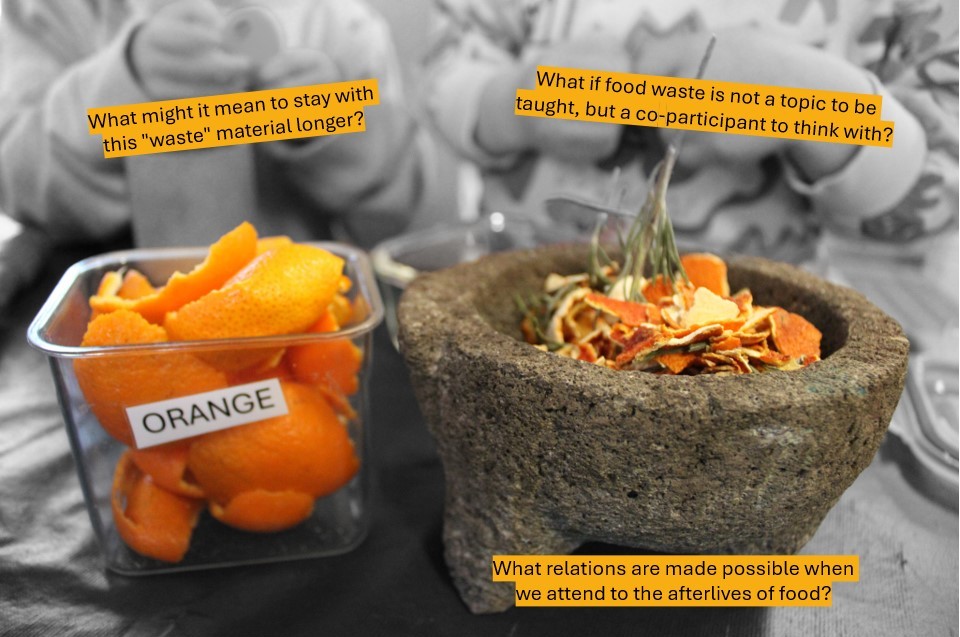

One day, a table in the classroom is set up with jars containing dried citrus, mint leaves, and cinnamon sticks—materials intended for a sniffing activity that invites sensory exploration. As the children pass the jars around and lift the scents to their noses, Holly pauses and asks, “Can we smash them?” An educator brings out a mortar and pestle, and the children smash and grind. They soon discover that the dried orange peels resist breaking down. This resistance opens a moment of attention and attunement. The peels push back. They refuse. And through this insistence, they begin to shape the inquiry.

In everyday educational contexts, orange peels are typically swept into the compost bin, or perhaps folded into lessons on environmental responsibility. Here too, knowledge is often positioned as the child’s ability to demonstrate the “correct” steps of composting or to sort waste into the “right” bin. This moment instead calls us to linger, to resist efficiency and certainty, and to dwell with something slow, situated, and uncertain.

The educators and I ask ourselves:

Staying with Orange Peels

After the first encounter, orange peels shift from being treated as food scraps to becoming thinking companions that live among us in the classroom. Children, educators, and I collect peels during snack and lunch times and bring them to the dedicated “orange peel table.” More than simply a surface, this table becomes a gathering place where children-educators-pedagogist-peels return to one another again and again, through conversations, shared noticing, and being with one another.

In those first weeks, the table comes alive with gestures. Hands move peels into pieces and piles. A citrus scent drifts across the room. Families pause and notice it when they pass by: “It smells so good in here!”

The orange peels complexify in meaning and become many different things: sugar, medicine, potion, and sprinkles.

Alex: We need these (orange peels) to grind. ’Cause they are our little sugar things. They are liquid and sugar.

She says this as she breaks the peels into little pieces.

On another day, the orange peels take on a new life and become medicine.

Alex: This is drying, and then after you dry it, it’s yummy to eat. But we are actually making medicine.

Each day, the peels draw us into new encounters. The children, educators and I pay attention to: What conversations are orange peels inviting/resisting us to be in? What ways of knowing are being opened when we stay with orange peels rather than discard them?

Holly: I cracked it.

Miya: This feels squishy. That one’s squishy too.

Holly: This makes my eye really sour.

Holly: It’s so juicy it sprayed in my eye! This one is so juicy. You can eat the juice!

Ayla: I can feel the juice!

Liv: I am smashing it into little pieces. Smell it.

Alex and Holly cut and grind the orange peels into small pieces. When a piece refuses to break down, Alex grunts with effort.

Lu: That one is really hard to cut, huh?

Alex: It’s ’cause it’s dry.

Later, Alex and Holly decide not to use the dried pieces.

Alex: ’Cause we don’t like the dry ones.

Lu: How come we don’t like the dry ones?

Alex: We don’t need the dry ones.

Holly: We can’t smash them.

These remarks are acts of noticing—attending to the material, its complexities, and its transformations.

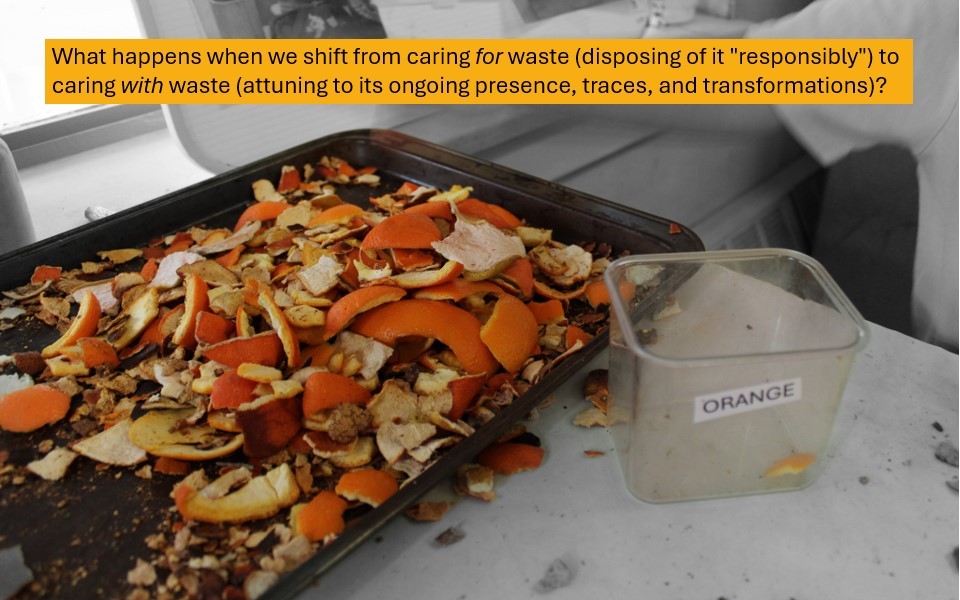

As the peels change, we find ourselves moving with their rhythms. The children touch, smell, and attend to the transformations taking place. Some children press the peels between their fingers to feel them stiffen and curl, and some line them up to notice how their colours darken. Educators, too, slow their pace, observing with greater care and dwelling with the quietly unfolding process. Together, we ask different kinds of questions, ones that are interpretive and speculative. Our questions attend to what gestures, materials, and encounters might be telling us, and we wonder what else could be possible in our relations with orange peels.

Some questions we think through and with are:

- How might orange peels invite us to rethink our relationships with waste, materials, and the more-than-human world, not as something to manage or dispose of, but as something to stay with?

- Rather than teaching children how to discard food scraps “responsibly,” what possibilities emerge when we shift from caring for waste to caring with it, attuning to its presence, transformation, and traces?

Together, children-educators-pedagogist attune to the peels’ rhythms to think, wonder, and live with their gradual transformations. In their decaying and decomposing states, the peels draw us toward possibilities beyond cleanliness, order, and disposal. Their resistance to being smashed becomes a provocation—a call to notice difference, to ask new questions, and to think otherwise.

Remaking an Orange

Several fresh spirals of peel lie across the table, coiling into circles. Holly picks up a long ribbon and examines it as she stretches, swirls, and twists it between her fingers. With each movement, the peel comes alive, dancing and bouncing in the air. No longer food waste, it is becoming something else.

Drawn into the rhythm of the peel’s motion, Holly layers the other long pieces one atop another. Her hands move with care, following the curves and resistances of each strip, guided by what the peel allows. At last, she takes the final piece and wraps it around the others, tucking the end in to hold them together.

Holly: I made an orange!

In her hands, a new form takes shape—an orange composed entirely of discarded parts, transformed through layering, holding, and intention.

Holly: My orange! This is the biggest orange in the whole entire world!

This moment is layered with pedagogical possibilities, opening space for experimentation and relational dialogue that helps us to think beyond how we previously thought orange peels or food waste. What does it mean to “remake” an orange? What is being invented here, not just materially, but relationally? These gestures move beyond accurate representation or naming parts such as rind, segment, pulp, or seed. They are experiments in reconfiguring relationships—with materials, with time, and with each other. The peels push back, slip, and fall apart. Holly responds by adjusting, rearranging, and making again. The act of remaking an orange becomes a relational dialogue—between child and material and between what holds and what resists. It is not a simple act of construction but a process of negotiation and listening through touch.

As Holly gathers the peels, presses them together, and tries to imagine how they might become whole again, she says, “It’s gonna fall off!” The pieces slip slightly apart and stick out from the whole. She pauses, then carefully holds them one by one and experiments with different ways of fitting them together. As she readjusts and rearranges the peels in her hands, feeling them relax, she exclaims, “There, there! That’s good, that’s good, that’s good!”

In this moment, a conversation between the peels and Holly unfolds through gesture and rhythm, between the press of fingers, the quiet rearranging, and the movement and resistance of peels. The peels yield and resist, sliding, falling, and settling into new relations. As hands gather, press, and stack, an orange is reimagined through dialogues composed in touch and tension.

Staying and thinking slowly with orange peels marks a powerful pedagogical shift—from doing to a material toward being with a material. Through such encounters, new curricular possibilities take shape where food waste becomes more than garbage and where the stains left behind are seen, not as messes to be cleaned, but as invitations to slow down, notice, and dwell in what takes shape.

Attending and Responding to Orange Peels’ Transformations

In this shared inquiry, the educators and I stretch our attention beyond the children’s words to the material presence of orange peels. We ask ourselves: How do we—children, educators, and pedagogist—listen and respond to peels?

Orange peels scatter and spread across the table in various states of transformation, some freshly torn and soft to the touch, others browned and curled, a few still charred. Fingers, hands, and wooden sticks meet the peels, pressing, tearing, and mashing. In the midst of this encounter, Holly pauses, holding up her hand for everyone to see.

Holly: My nails are turning orange! I just break the pieces. And then I rub the juice.

Holly: If you play with the oranges a lot, they will …your fingers will get orange.

Lennon: You need a big one and make it into a small one by mashing it. And you need to mash so hard to make more colour.

Holly’s and Lennon’s words draw our attention to the transfer of colour and to the intimate, lingering relation among skin, hands, and peel. The orange does not stay still. It stains, it steeps, and it transforms the bodies that encounter it. Through repeated encounters—grinding, pressing, smashing—materials respond in new ways. These ongoing encounters invite children and educators to notice subtle shifts and transformations and to deepen their relationships with the orange peels.

At the table, marks emerge. Juicy streaks, powdery trails, and crumbly specks spread across the paper and table. The children make marks with orange peels, hands, fingers, nails, and wooden sticks. Each gesture carries its own intention, and each peel responds in turn. Fresh peels release bright yellow juice that soaks into the paper. Older, dry peels crumble into chunks and flakes. Burnt peels leave soft, dark powder. Each trace tells a different story of time, decay, and possibility.

Rolling Orange Peels

The peels invite more than just smashing—they call to be rolled. Through their shape, resistance, and movement, they compose a choreography of gestures: hold, twist, tuck, press.

As Ayla begins to roll orange peels, she quickly finds out that the elastic used to hold the rolls together won’t stretch over her rolled peel.

Ayla: Too big, too big!

She pauses, unravels the peel, and rolls again, this time rolling it tighter. But the rolled peel still exceeds what the elastic can hold and bounces off.

Ayla: Too medium!

She unravels the whole thing again and begins tearing off small pieces from one end, adjusting with care. Then, slowly and attentively, she rolls again.

Ayla: Okay, okay. Try not to break it.

Moments later, Ayla shows me the tightly rolled orange peel, wrapped snugly in an elastic band.

Ayla: Look, I made a rose!

In the gentle rolling, unrolling, and rerolling between fingers and peel, the children listen closely, pressing the peels into form and being pressed in return. Rolling, in this context, becomes an act of attending and responding to the material’s gestures.

Cracking Orange Peels

As children-educators-pedagogist stay with the orange peels over time and attend to their slow transformations, we notice that the peels’ once-bright skin slowly fades to muted tones of amber and brown. The juicy and pulpy skin stiffens and curls at the edges. A few dried peels roll from the table onto the floor. Nearby, Lennon shifts her body as she stays at the orange peel table. A sudden crack interrupts and catches her attention. She looks down to see that she has stepped on a peel, now splintered into tiny pieces beneath her shoe.

Lennon: I crack the orange peel.

Lu: How did you crack the orange peel?

Lennon: With my foot.

From this accidental encounter, a new invitation emerges. Other children drop dried orange peels onto the floor, this time with intention. Soon the room fills with crisp snaps as children stomp, jump, skip, slide, spin, and fall on the peels. In this moment, the dried peels invite bodily movements that extend onto the floor.

Gathered around the orange peel table, children and educators attune and listen deeply to the peels’ gestures, calls, and marks.[1] The orange peels remind us that food waste continues even when it slips from sight—it stains, lingers, and transforms. Attending to these traces opens pedagogical possibilities where materials speak, where waste becomes a site of inquiry, and where children’s engagements prompt us to rethink our relations with the more-than-human world. Our questions shift from “What can I do with this material?” toward “What is this material saying?” and “How is it asking me to respond?”

These glimpses of encounters with orange peels are significant because they unsettle the usual logic of sensory activities. Such activities are often designed so that children engage their senses. They are considered successful when children correctly name what they see, smell, or touch. Knowledge, in this frame, is positioned as individual recognition—a matter of accurate identification. The orange peels, however, invited us to pause and attend differently. Knowledge was composed through relations, through noticing how the peels resisted, stained, and transformed, and how these gestures called us into shared inquiry.

This shift—from doing something to being with a material—echoes the pedagogical orientation of creating conditions where curriculum unfolds through relations rather than predetermined outcomes. It invites educators to linger with uncertainty, to listen to what materials ask of us, and to think of pedagogy as something composed collectively with children, materials and place. The inquiry does not end here; it carries forward in the everyday gestures, stains, and questions that continue to shape our pedagogical work.

[1] Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, Sylvia Kind, and Laurie L. M. Kocher, Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education, 2nd edn. (New York: Routledge), 2024.