Keywords

Relational Languages of Mark Making

with support from ECPN leadership team – Adrianne Bacelar de Castro & Kathleen Kummen

This blog post traces how engaging with mark making opens spaces to notice and think with the dynamic interplay between collective inquiry and individual expression. It considers how children’s interactions with materials and each other raise ongoing questions about the environments we create and the ways they influence communication and relational practices.

What does it mean to make a mark?

This question guides my work alongside educators and children at the Central Vancouver Island Multicultural Society (CVIMS), a nonprofit organization supporting newcomers and refugees. In this context we engage with how children relate to one another, their environments and the materials they encounter. We chose the term mark making rather than drawing to acknowledge the diverse possibilities within materials—the gestures, textures and traces[1]—through a relational lens. Through mark making, we notice how children’s gestures and interactions reveal possibilities for shared thinking and collective inquiry, while also unsettling the ways mark making is often organized in early childhood settings—as an activity of individual output rather than a relational process.

At CVIMS, the children’s program is grounded in the organization’s commitment to equity, diversity, inclusion and respect for all peoples. Rooted in these commitments, we ask: How can mark making become a collective language rather than an individual task? This question led us to consider how marks unfold in early childhood spaces shaped by children’s diverse languages, histories and ways of being together.

Carlina Rinaldi suggests that what emerges in children’s mark making is not simply the outcome or final product but the ongoing process of shared meaning making that unfolds through relational encounters.[2] In this view, learning is not a solitary act but a social and collective process, a negotiation of meanings emerging from the interactions among children, educators and materials. Attending to mark making through this lens invites pedagogical possibility: How might mark making foster collaboration? And when do they risk reinscribing narratives of individualism?

To stay with these questions, we attune to what Loris Malaguzzi, founder of the Reggio Emilia approach, described as the “hundred languages” of children—a metaphor for the many ways children express themselves, think and relate to the world.[3] By attuning to these “hundred languages,” we listen to how children communicate through materials, movements, gestures and collective mark-making processes, foregrounding ways of relating that extend beyond verbal language. Through this work together, we aim to nourish communication that transcends conventional representation, moving beyond traditional forms of expression and the dominance of the English language.

How Might Abundance Risk a Relational Practice?

Since January 2023, guided by the B.C. Early Learning Framework[4], educators and I have been experimenting with this extended inquiry into how children engage with their world through mark making. The Framework’s commitment to intentional, responsive and relational pedagogy informs our ongoing work. Together we ask: What does it mean to make a mark? This question emerged collaboratively from our shared reflections on how children’s gestures, materials and movements contribute to a language of communication beyond words.

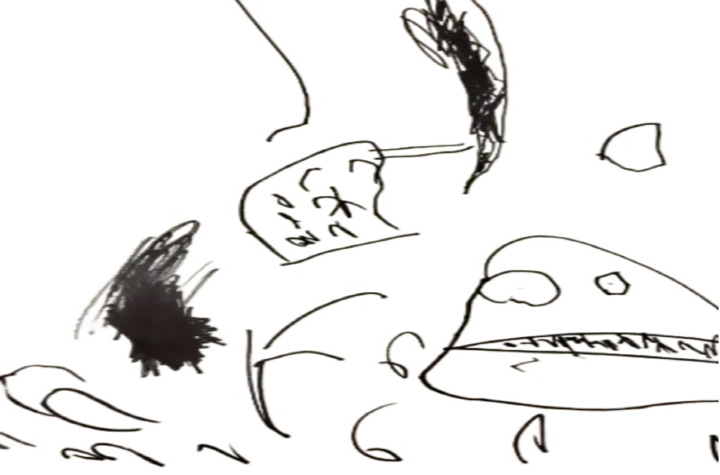

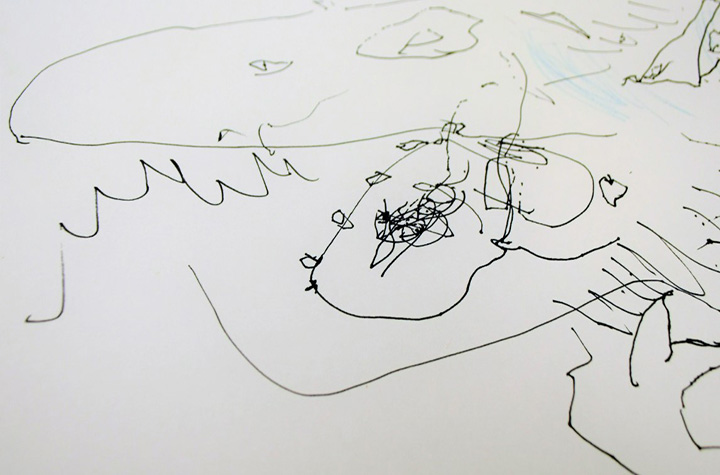

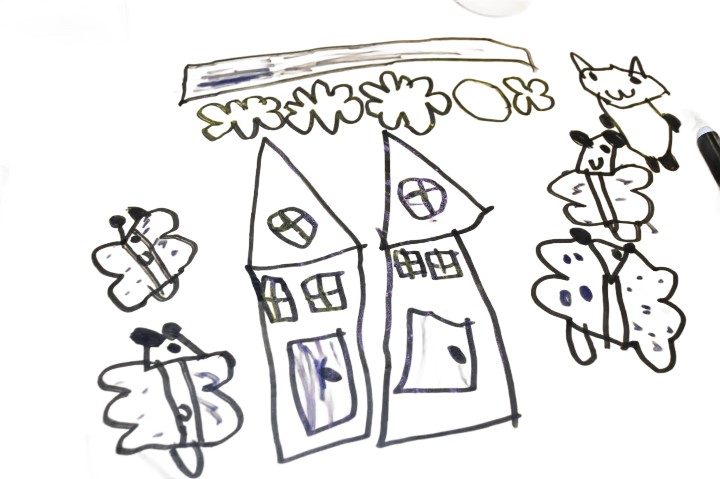

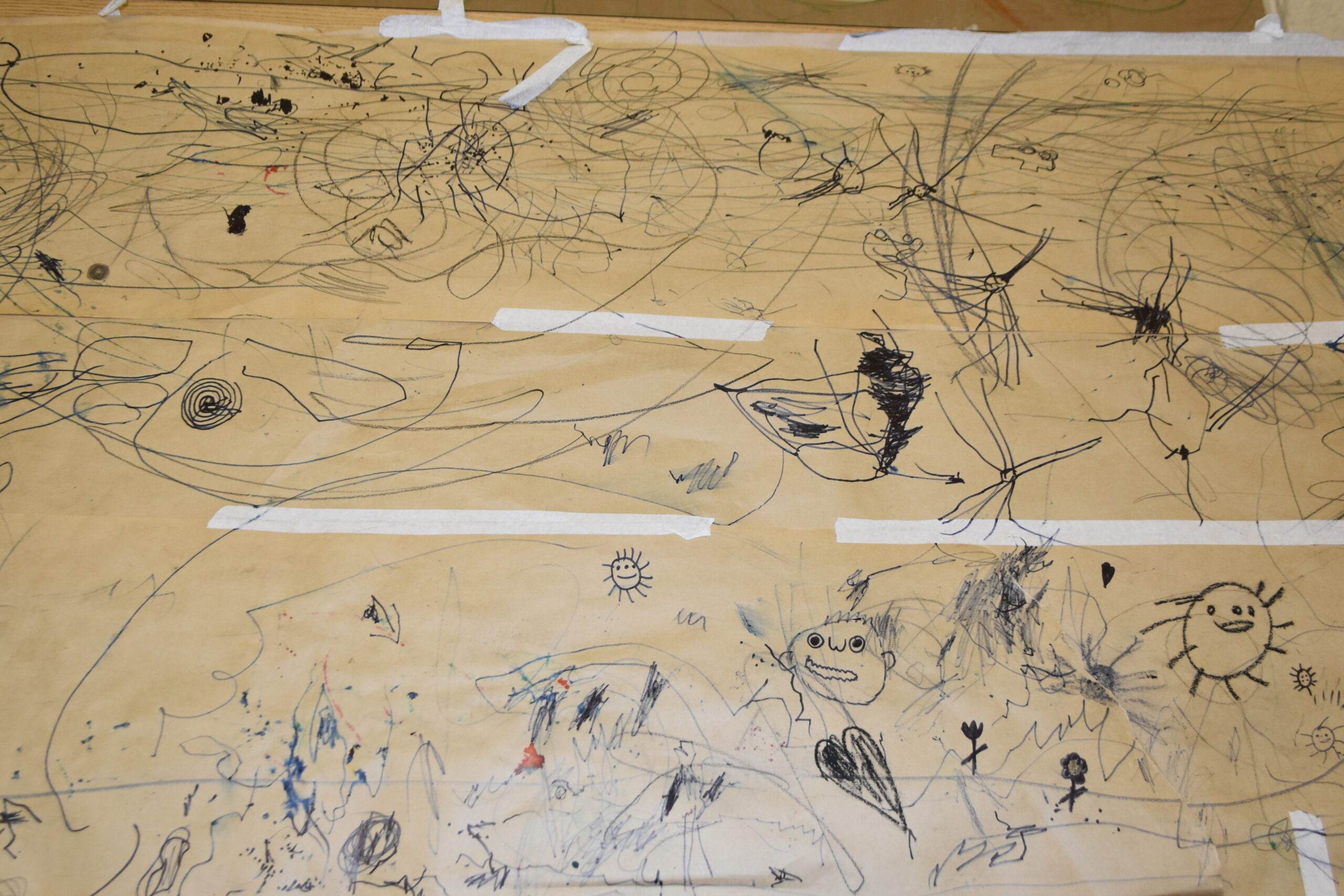

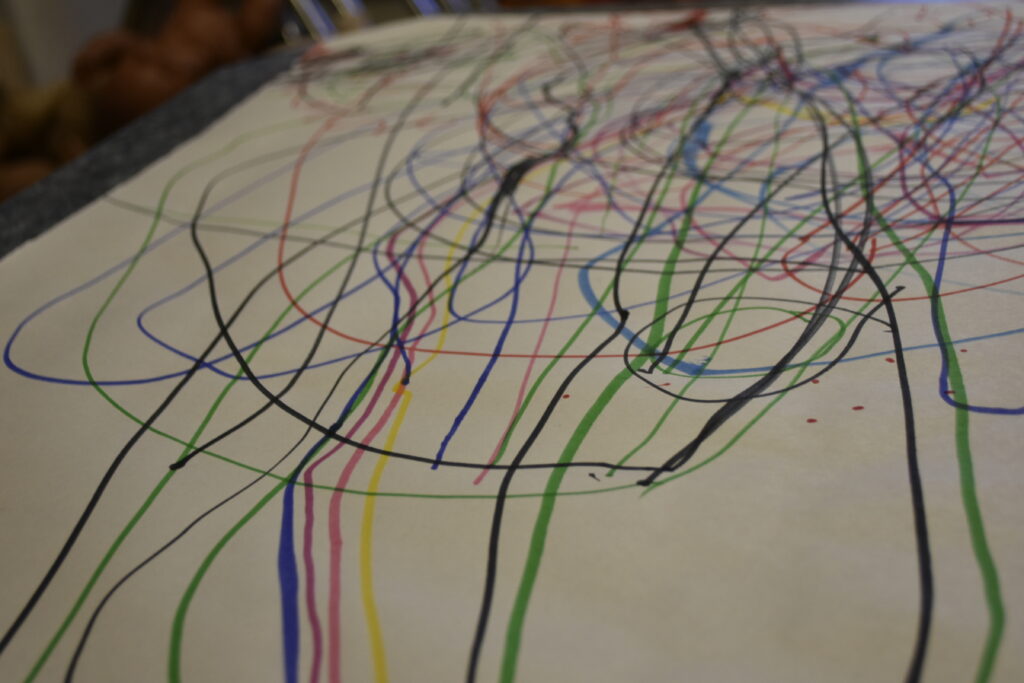

In this inquiry we introduce large sheets of paper and cardboard as communal spaces where children gather to make marks. Our intention is to create conditions where children’s relations with materials, with each other and with the environment can unfold through ongoing interactions and without predetermined outcomes. For over a year, these large sheets of paper and cardboard become spaces for collective mark making. Children come together, connecting bodies, feet, hands and fingers with various assemblages of materials: paint, pastels, fine liners, watercolour, chalk, Q-tips, brushes, felt pens, charcoal, crayons, permanent markers and coloured pencils. These materials accumulate gradually, offered by educators, brought in by families and found in and around the classroom. Over time, as children communicate with and through materials and one another other, we carefully document moments shaped by the relationality among children, materials and the environment.

In this inquiry we introduce large sheets of paper and cardboard as communal spaces where children gather to make marks. Our intention is to create conditions where children’s relations with materials, with each other and with the environment can unfold through ongoing interactions and without predetermined outcomes. For over a year, these large sheets of paper and cardboard become spaces for collective mark making. Children come together, connecting bodies, feet, hands and fingers with various assemblages of materials: paint, pastels, fine liners, watercolour, chalk, Q-tips, brushes, felt pens, charcoal, crayons, permanent markers and coloured pencils. These materials accumulate gradually, offered by educators, brought in by families and found in and around the classroom. Over time, as children communicate with and through materials and one another other, we carefully document moments shaped by the relationality among children, materials and the environment.

When revisiting the pedagogical traces, we notice that the collective mark-making spaces can carry a sense of curiosity, rhythm and repetition. At the same time, the growing abundance of materials becomes unsettling and invites us to pause. The educators frequently encounter catalogues and magazines promoting an ever-growing selection of materials as essential for “quality” programs. In many early childhood settings, the idea that providing more materials enhances program “quality” persists, influenced by dominant educational discourses and market-driven assumptions.[5] These discourses of material excess and standardization invite us to consider how such abundance shapes our pedagogical decisions and relationships with children. When materials become a measure of quality, the focus can shift toward consumption and accumulation, narrowing attention and drawing energy away from the relational and intentional experiences that nurture collective learning. As choices multiply, we wonder how this abundance shapes the nature of children’s encounters with mark making.

When revisiting the pedagogical traces, we notice that the collective mark-making spaces can carry a sense of curiosity, rhythm and repetition. At the same time, the growing abundance of materials becomes unsettling and invites us to pause. The educators frequently encounter catalogues and magazines promoting an ever-growing selection of materials as essential for “quality” programs. In many early childhood settings, the idea that providing more materials enhances program “quality” persists, influenced by dominant educational discourses and market-driven assumptions.[5] These discourses of material excess and standardization invite us to consider how such abundance shapes our pedagogical decisions and relationships with children. When materials become a measure of quality, the focus can shift toward consumption and accumulation, narrowing attention and drawing energy away from the relational and intentional experiences that nurture collective learning. As choices multiply, we wonder how this abundance shapes the nature of children’s encounters with mark making. A tension emerges: The abundance of materials that we first understood as offering multiple possibilities for relation begins to risk dispersing attention and pulling children, and educators, toward more individual encounters. While we initially saw the encounters with a variety of mark-making materials as rich and complex, we start to ask whether what appears as complexity might in fact reflect a kind of saturation.

A tension emerges: The abundance of materials that we first understood as offering multiple possibilities for relation begins to risk dispersing attention and pulling children, and educators, toward more individual encounters. While we initially saw the encounters with a variety of mark-making materials as rich and complex, we start to ask whether what appears as complexity might in fact reflect a kind of saturation.

The Hundred Languages: Materials as Relational Participants

This thinking deepens our commitment to honour children’s hundred languages, recognizing that communication extends beyond spoken words and is alive in the relationships among children, materials and the environment. This perspective invites us to consider how materials are active participants in these communications—not merely tools but dynamic elements that shape and are shaped by relationships. Rather than viewing materials as neutral or passive, we see they are entangled in ongoing relations with children and educators, shaping interactions and opening pedagogical possibilities.[6] The B.C. Early Learning Framework similarly calls on educators to intentionally select materials that offer diverse possibilities for communication and experimentation.[7] While this might seem to suggest an abundance of choices, we understand it as a call to thoughtfully curate materials that open space for deeper connection. In response, we experiment with reducing our offerings, introducing only sheets of white paper and black markers. This narrowing creates space for us to slow down and engage with mark making more intentionally, inviting us to listen more closely to the languages expressed through the making of marks and to attune ourselves to the possibilities that arise in shared encounters.

Listening with Less

Yet, as we continue, we notice how even minimal materials can unintentionally reinscribe the logic of individual productivity rather than fostering collective inquiry. While the classroom initially felt more intentional, it begins to mirror a pervasive logic of “more is better” that we had sought to challenge. What at first feels like clarity reveals familiar rhythms of individual production. Children sit around the same large sheets of paper, but each with their own marker and task—a quiet return to a “more is better” logic, not driven by material abundance this time but by the pressure to produce something recognizable and finished. In reducing the materials, we risked recentering the product over process, drifting away from the relational, unfinished and collective nature of our inquiry and shifting focus back to end-products rather than the evolving relationships among children, materials and each other.

These wonderings do not offer solutions but generate new provocations for us as educators:  What does it mean to create spaces for children to think together? How might materials—whether abundant or simplified—support or disrupt shared encounters?

What does it mean to create spaces for children to think together? How might materials—whether abundant or simplified—support or disrupt shared encounters?

Through narrowing our focus to black and white materials, we were not seeking answers but a way to stay with these questions differently. This shift made it possible to attend to the finer details of mark making and deepen our thinking on the role of materials in shaping the relational life of the classroom. In their simplicity, these materials invited a slower pace, a different kind of listening and moments of quiet attention to lines, gestures and the spaces between them.

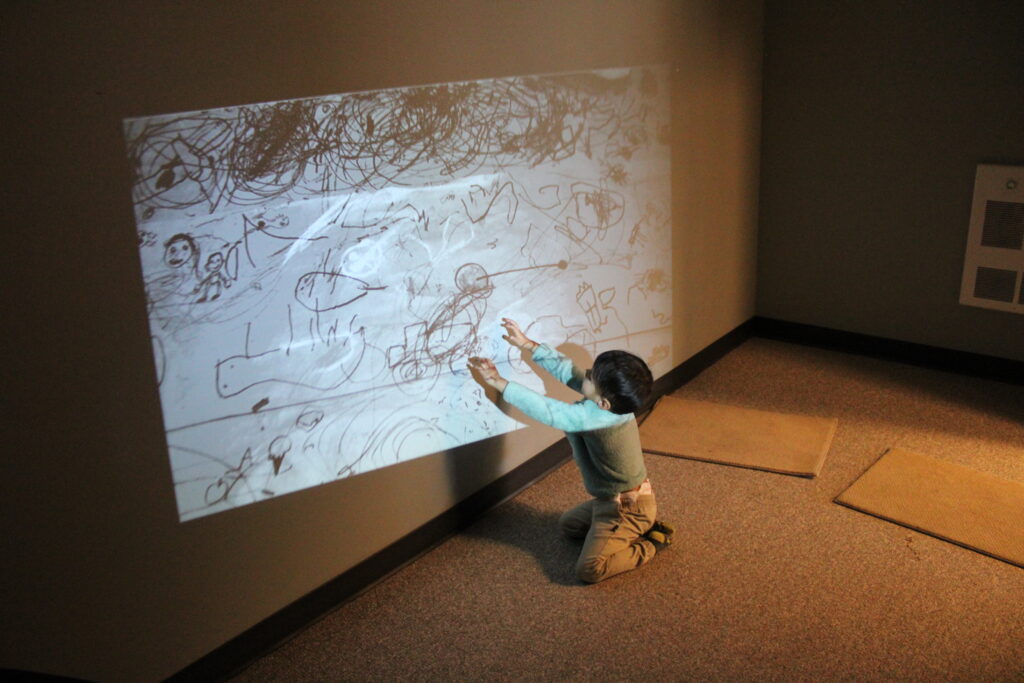

The redistribution of materials becomes its own kind of relational act. While we stay with the simplicity of markers and paper, other materials that no longer seem to foster thoughtful, diverse or collective relations are gently gathered by the children and educators and offered to families for repurposing during an open house in December. The gathering invites families to share in the children’s work, enjoy cookies made by the children, dance, sing and view the documentation of marks created in the classroom. This act of redistributing materials sparks new possibilities for co-creating marks and invites us to rethink the life and transformation of materials within the classroom.

Staying With Material Relations

When we see materials as active participants in the co-creation of relational spaces we are also confronted with our ongoing reliance on consumable materials like large sheets of paper and cardboard. Over the years, our inquiry has depended on consuming these materials in the name of mark making—raising questions about how we are complicit in extractive and linear material relations, a tension also taken up in re:materia, a project that reimagines our relationships with materials. We do not approach these questions looking for resolution, but as a way of thinking with children through the complexities of our material practices.

We wonder how staying present with materials might shape our relationships with them and with one another. We start to experiment with how materials live in the classroom—remaining attentive to what was already there and inviting those materials to remain present with us.

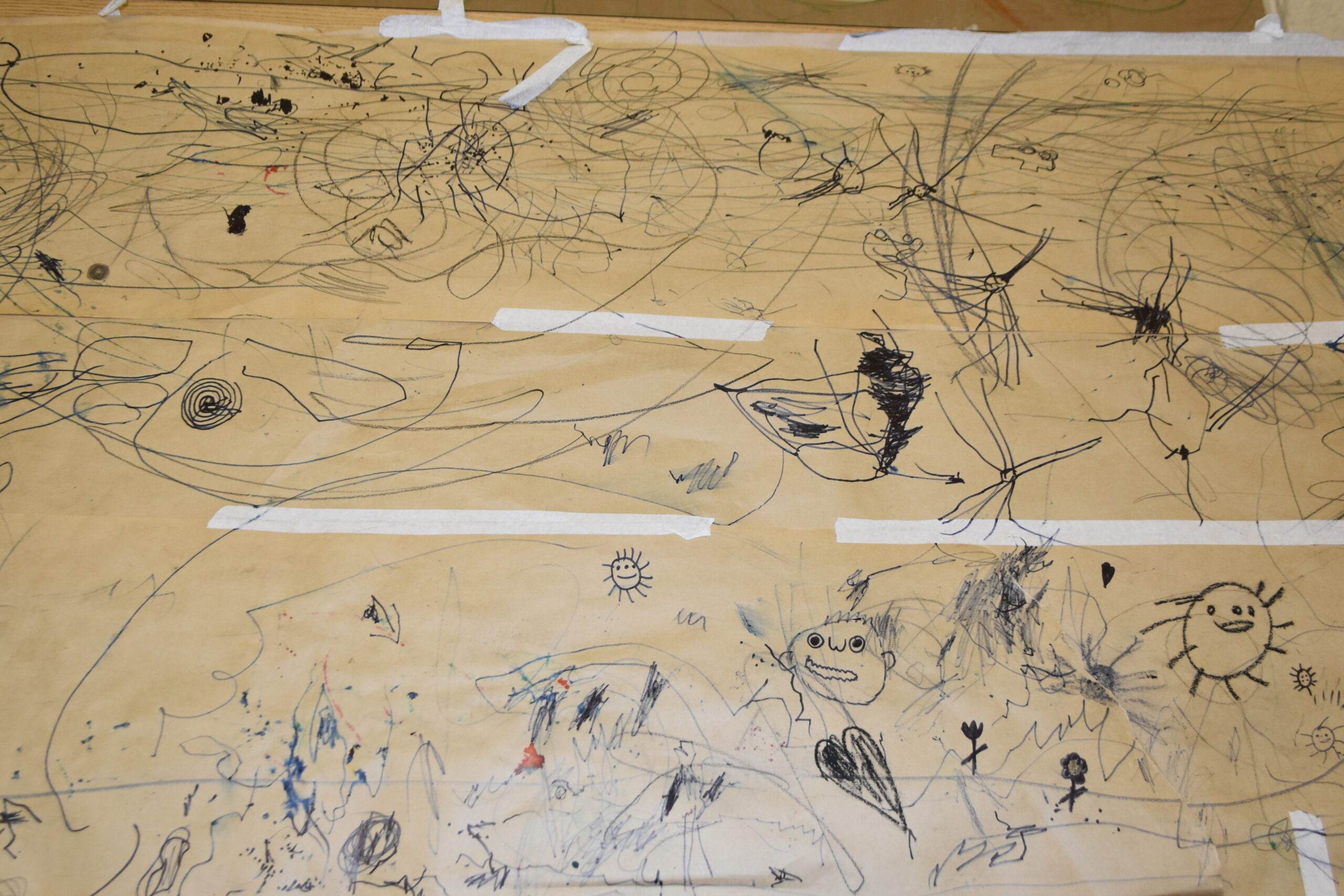

We wonder how staying present with materials might shape our relationships with them and with one another. We start to experiment with how materials live in the classroom—remaining attentive to what was already there and inviting those materials to remain present with us.  Rather than discarding the remnants of paper covered in marks, we choose to live with them. The same sheets of paper, once destined for recycling, remain in the space as children continue to add marks, overlapping and tracing over previous ones. The recycle bin, overflowing with marked paper, is no longer emptied. Instead, children gather around these materials in new ways, tearing and cutting the scraps of marked paper into smaller pieces. These materials live with us, no longer treated as waste but as active participants in the life of the classroom. Over time the sheets of marked paper tear and soften underfoot, and the scraps in the recycle bin are torn to tiny particles offering new forms for experimentation. Water, a regular companion in ECE settings, enters the conversation from a nearby sensory table, transforming remnants into pulp and marking the beginning of a ritual of making paper—a tactile and temporal act that invites us to participate in cycles of creation and re-creation.

Rather than discarding the remnants of paper covered in marks, we choose to live with them. The same sheets of paper, once destined for recycling, remain in the space as children continue to add marks, overlapping and tracing over previous ones. The recycle bin, overflowing with marked paper, is no longer emptied. Instead, children gather around these materials in new ways, tearing and cutting the scraps of marked paper into smaller pieces. These materials live with us, no longer treated as waste but as active participants in the life of the classroom. Over time the sheets of marked paper tear and soften underfoot, and the scraps in the recycle bin are torn to tiny particles offering new forms for experimentation. Water, a regular companion in ECE settings, enters the conversation from a nearby sensory table, transforming remnants into pulp and marking the beginning of a ritual of making paper—a tactile and temporal act that invites us to participate in cycles of creation and re-creation.

Gesturing Towards a Collective Language

These interwoven threads story our commitment to attuning to the many languages of children—both their spoken language and their material relations. Through mark making, we aim to nurture communication that moves beyond conventional forms of representation, challenging the dominance of traditional communication and the English language.

As our inquiry unfolds, we hold onto the tension between collective inquiry and individual expression that opened this work. For marks to stay in conversation, questions emerge for us around the role of material abundance: What becomes possible, and what becomes less visible, when too many things are happening at once? The shifting relations among children, materials and educators reveal mark making as a shared language—one that creates complexity, holds relations and unsettles individualistic and consumptive narratives.

We return to the question grounding our inquiry: How can mark making become a collective language rather than an individual task? At the same time, we are invited to reflect on how pedagogical choices shape or unsettle dominant narratives of individualism, consumption and excess. How might we, as educators, create spaces where children relate to one another, to materials and to the world in ways that honour interconnection and shared responsibility?

These questions remain open, living provocations that guide us in our daily work together.

[1] Sylvia Kind, “Material Encounters,” International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies 5, no. 4.1 (2014): 865–877, https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs.kinds.5422014.

[2] Carla Rinaldi, Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners (Reggio Children and Project Zero), 2001.

[3] C. P. Edwards, ed, The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education (New York: Ablex), 1993.

[4] Government of British Columbia, British Columbia Early Learning Framework (Victoria: Ministry of Education), 2019.

[5] Gunilla Dahlberg, Peter Moss, and Alan Pence, Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Languages of Evaluation, 3rd edn (New York: Routledge).

[6] Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, Sylvia Kind, and Laurie L. M. Kocher, Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education, 2nd edn (New York: Routledge), 2024.

[7] Government of British Columbia, B.C. Early Learning Framework, 23.