Around the Vessel

- Home

- Field Notes

- Around the Vessel

Keywords

Supported by the ECPN leadership team

Children: Eleanor, Thea, Landon, Rafael, Tarik, Grady, Alaina, Mabel, Tabitha, Amy, David, Lydia*

What happens when we stay with the challenges of collective making, rather than focusing on individual expression? In the 3- to 5-year-old program at an early childhood centre in central BC, clay becomes more than a material—it becomes a gathering place for ongoing experimentation, hesitation, care, and tension. We do not set out to make a finished product. Instead, through repeated invitations to return to clay, we ask: What does it take to make something shared? What does it mean to let go of “mine”?

This field note doesn’t trace a single project or outcome. Instead, it follows moments where children work with and against each other, where ideas accumulate and fall apart, and where clay refuses to cooperate in predictable ways. What emerges is a story of staying inside the difficulty of building something together.

Beginning with clay: Ownership and collectivity

As a pedagogist, I try to create conditions where children can encounter the intricacy of working collectively, with the complexities of staying with the mess and unruly parts of living together.[1] Clay supports this work. It invites slowness, demands care, and always remembers what came before. We keep returning to it, not to repeat the same activity, but to linger inside the same questions.

Our work with clay began more than a year and a half ago and has slowly unfolded across many moments, encounters, and returns. In those early gatherings, large blocks of clay joined the group at the table. Hands squeezed and twisted. Earthy smells infused the room. Slowly we became aware of clay’s movements and sounds. We learned what clay needed from us at the end of our weekly encounters so that we could meet again. Clay was collected in a bag and snuggled safely in a container. Tables and hands we washed with basins of water, the clay slurry poured onto the grass outside so it would not get trapped in the plumbing.

During one of these encounters, a child commented that a group of individual clay pieces on a tray “looked like a city.” This sparked the collective construction of a metropolis. As the children built, it became clear that many children remained attached to the parts they had made. Discussions about who had made what circulated. Space was negotiated. Ownership was named. Although the city appeared to be a shared structure, it remained a collection of individual pieces. What holds a collective form, and what pulls it apart?

A small coil bowl was created and added to the city. Some children asked how to make one too. I wondered out loud: “Could we make a bowl together?” We talked about what a bowl needs—how it holds, how it grows, what the clay might ask of us. Over many weeks, something vessel-like took shape. We said it belonged to everyone. We agreed to add only little bits at a time, pressing gently into what already existed. After each encounter we carefully put our growing vessel into a humidor or wet-box—a five-gallon pail with a layer of plaster in the bottom that maintained the clay vessel in a pliable state until the next time we wanted to work on the bowl. Then, one day, we opened the pail where the bowl rested. It had collapsed into a pile of pieces. No one said anything right away.

I resisted the urge to fix the bowl myself, and we discussed what the children thought should happen next. Some children suggested squishing the clay back into a ball. Others wondered if we could piece it together again. There was a long pause. Then someone said, “Let’s make another one.” A few children nodded. There was no vote or decision made exactly; we just knew we would come back to the clay and try again.

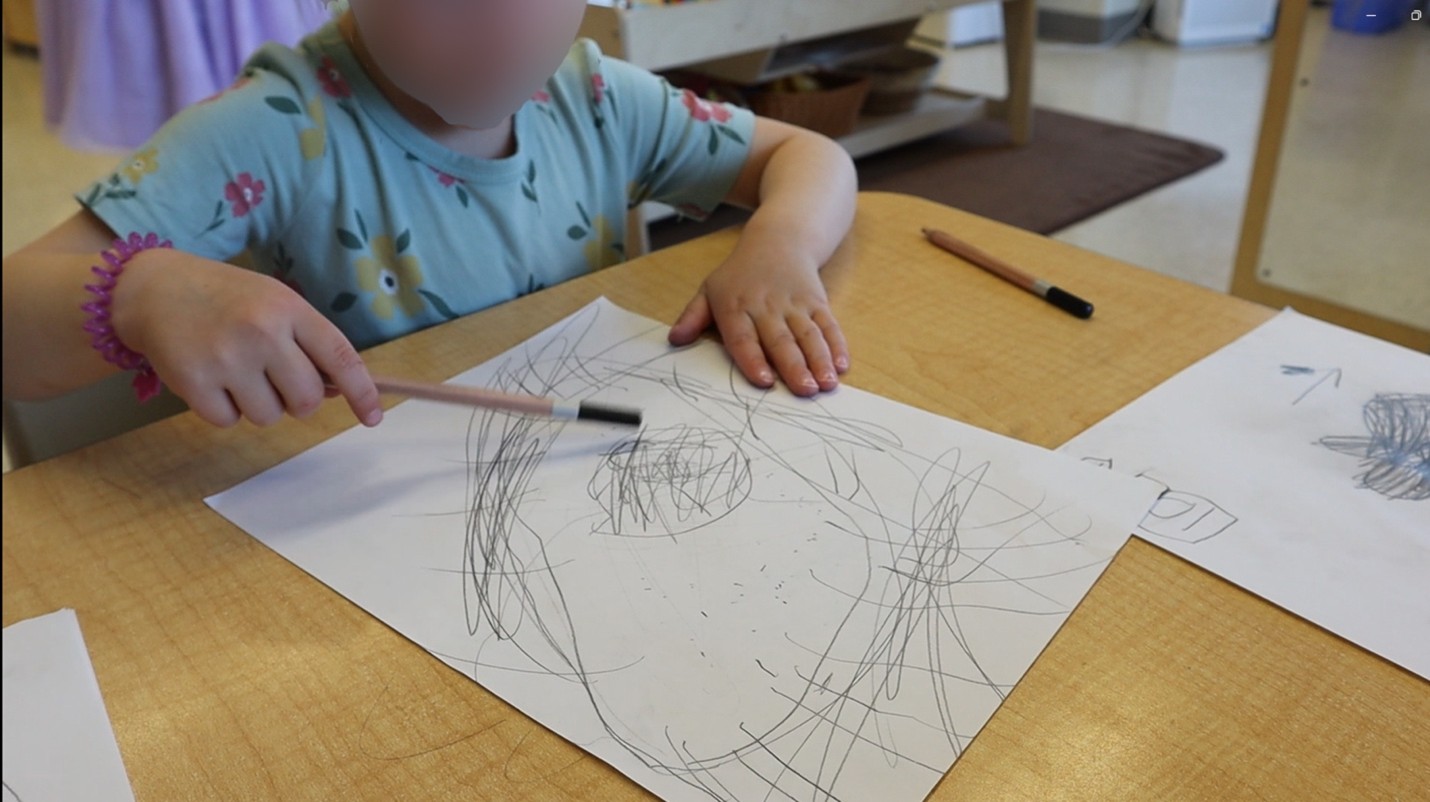

Supporting the new vessel: Thinking with drawing

When we gather again, we don’t start building right away. We sit with the idea of a new bowl. There’s talk about what went wrong—why it might have fallen, what it needed that we didn’t give. I bring out paper and pencils, thinking that maybe drawing could help us imagine another way. The children begin sketching.

Eleanor* draws a bowl with small legs. “So, it doesn’t fall down,” she says.

Thea holds up a sensory tube while pointing to her drawing. “Put it on this so it stays up. These are all the instructions.”

Other drawings follow. Some show flat pieces of clay holding the sides; others layer bowls inside bowls. The sketches feel tentative, full of care. They don’t give us answers, but they help us stay with the question.[2]

Building together again

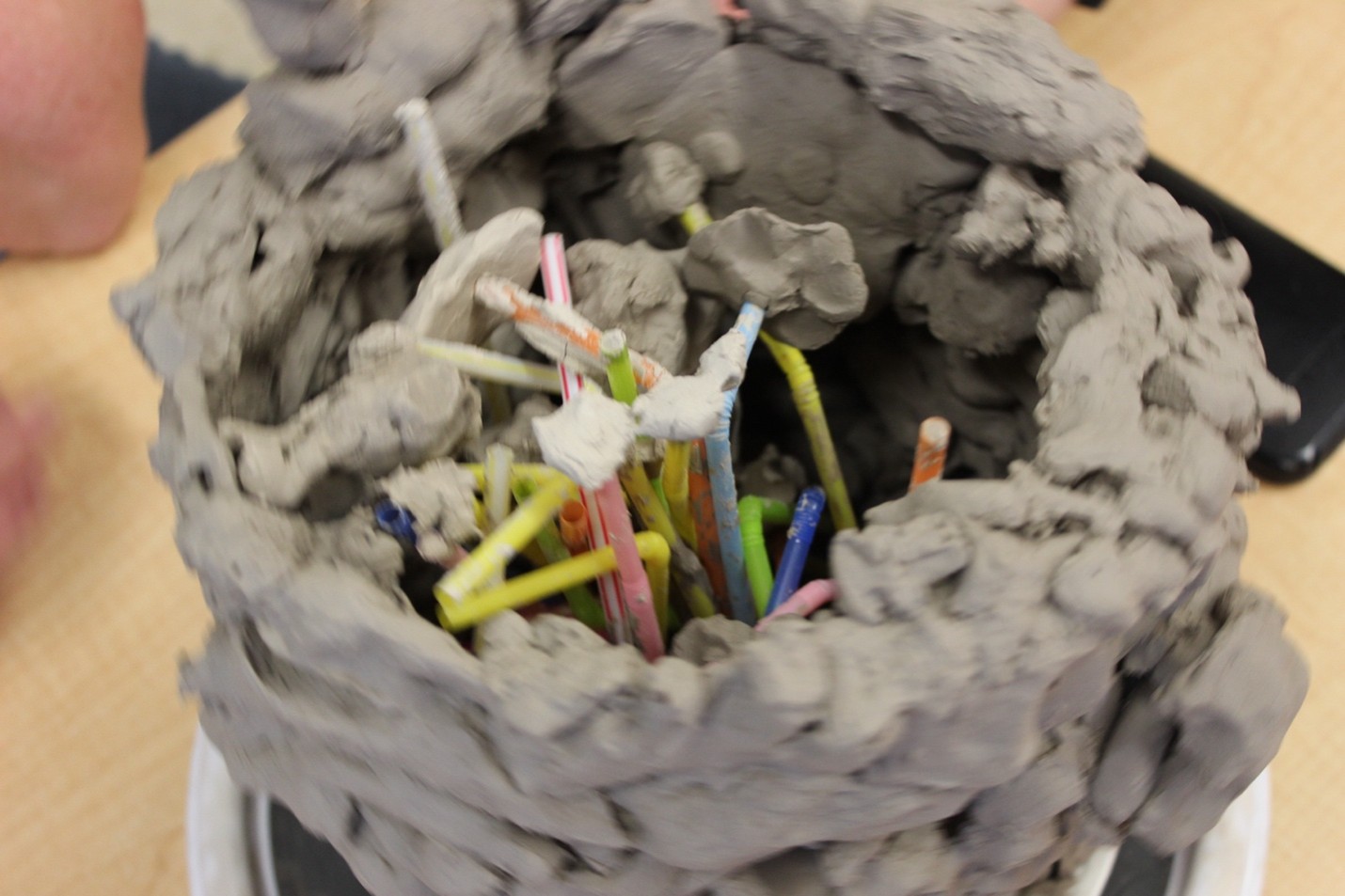

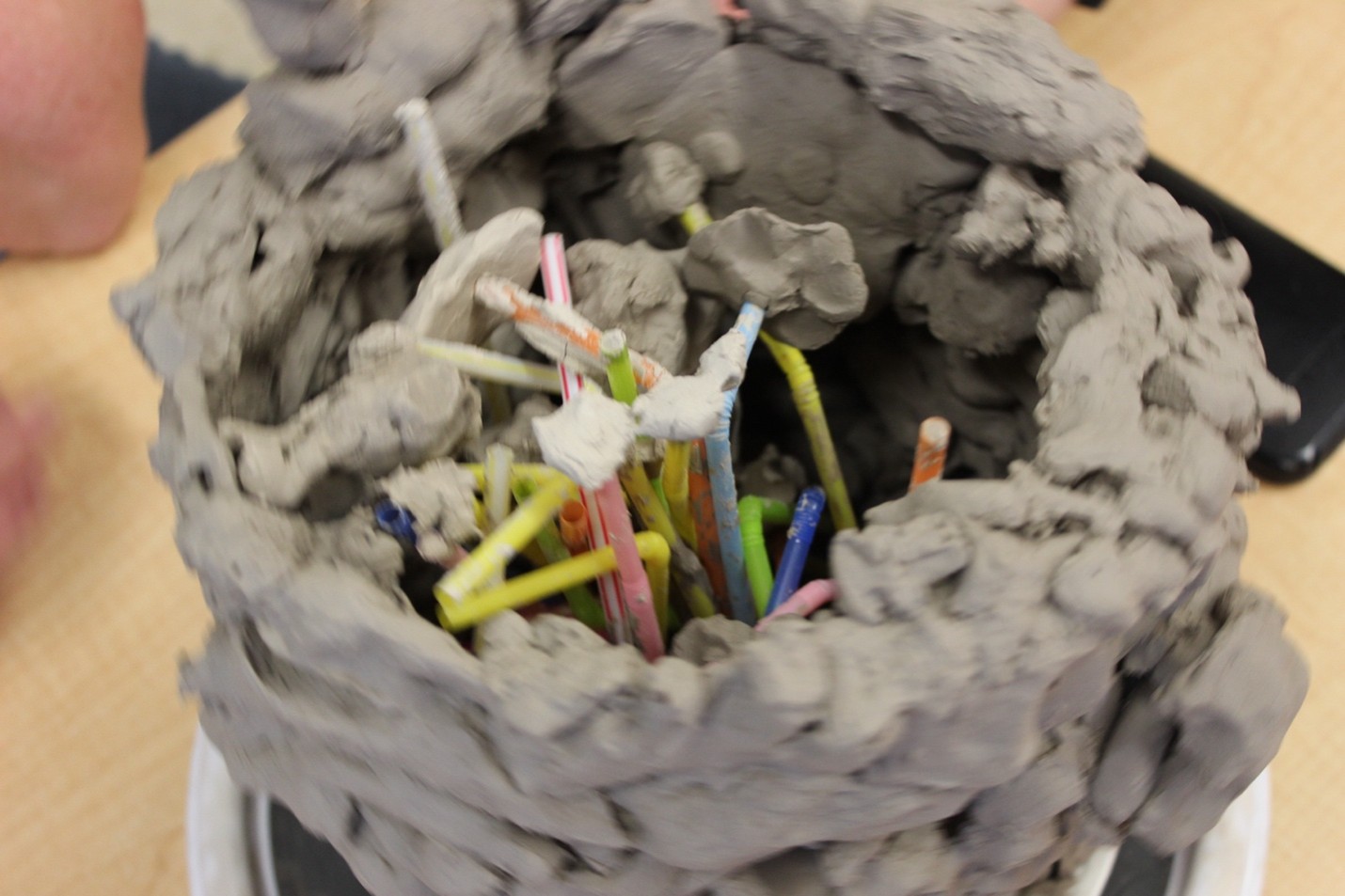

We return to the children’s drawings—sketches full of ideas for how to keep the bowl from falling—and begin again with the base from the first vessel. Small bits of clay are added around the perimeter, slowly, carefully. We offer the materials from their drawings: sensory tubes, paper rolls, and plastic straws. The straws, thin and upright, draw the children in. They name them necessary. The straws hold—for a while. But as more are added, they begin to lean outward, pulling against each other. The bowl’s centre grows crowded. We wonder: How many can it hold? The straws slump. They ask for something, too. Attention shifts—back to the clay, back to the walls. The materials are not passive here. They press back.[3]

How big is too big?

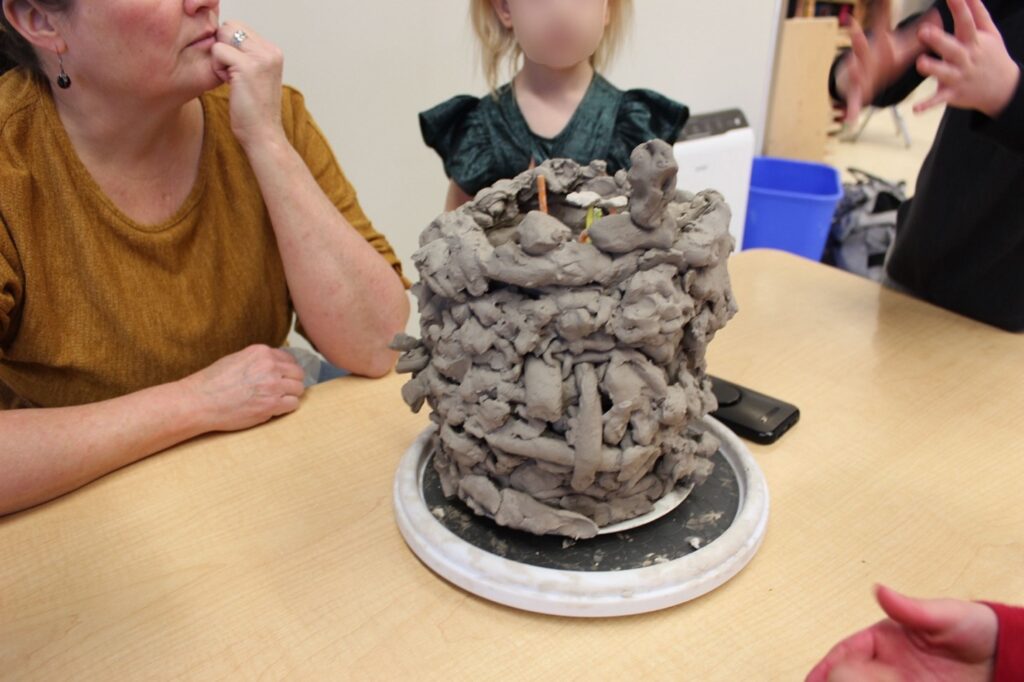

Piece by piece, the walls rise. Balls, snakes, flowers, cameras, Christmas lights—each added by different hands, each pressed gently into what’s already there. The bowl doesn’t follow a plan. It grows through accumulation, through gesture, through response.

“It’s going to be huge.… We’re making it huge,” says Thea.

“Up to the roof!” says Landon.

“Is the bowl ever going to be done?” I ask.

The children giggle and keep building. They flow in and out of the space. Some pause, some return. Those who have been with the clay the longest guide others, not with instructions, but through small demonstrations of care.

“Put little things on it and it doesn’t fall down,” Rafael says, tapping the edge.

The clay holds—for now. Its softness slows the pace. Its weight invites care. As hands work, conversations unfold: a weekend memory, a new sibling, a snowplough seen that morning. The bowl becomes a site for stories, for slowness, for gathering.

Over time, the walls sprout upward. Someone notices—the straws are gone from sight.

“It’s covering the straws now,” Alaina says.

“I think it’s going to fall,” Eleanor whispers. “Thea! Do you think it’s going to fall down?”

“Yeah.”

“So we got to be careful.”

Amy joins us at the table. “Hey—where are the straws?”

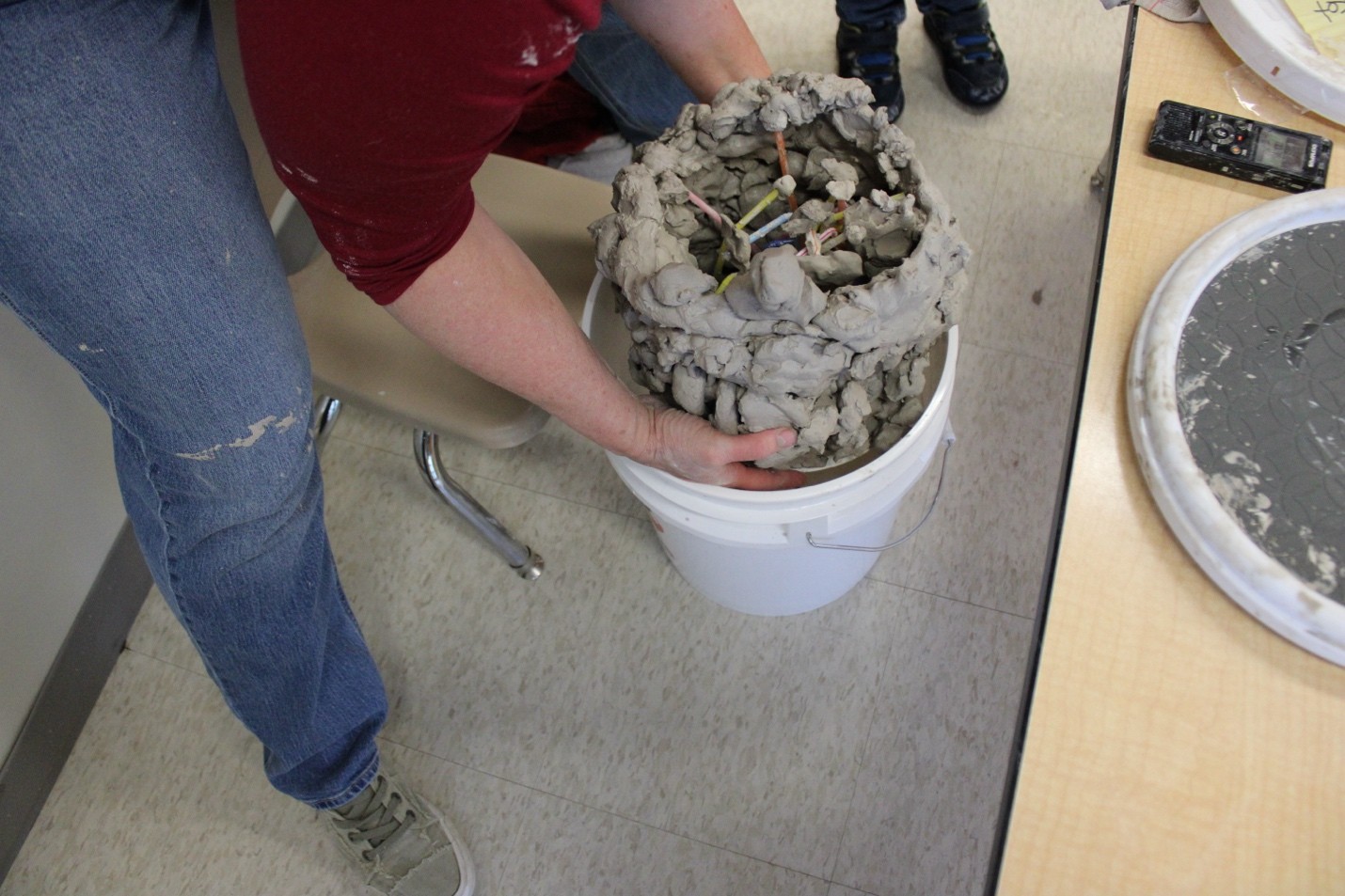

When it comes time to put the vessel back in the humidor, we realize it’s too big. It won’t fit. We pause. The vessel has outgrown the space we made for it. We don’t rush to a solution. Instead, we turn to the group and ask: What now?

“Should we try one more time to get it into the bucket?” I ask.

“Yeah,” the children reply.

I begin to lower the vessel. One child whispers, “Careful … careful … careful.”

“It will collapsilate!” Rafael warns. “We should probably let it get hard and leave it here.”

The others agree. We find a safe spot. The vessel stays—too soft to be moved, too big to be contained.

Worries

The children and I gather around the table. In the middle is the drying vessel on a rotating tray.

“It is already dry!” says Mabel.

“It’s so dry,” adds Eleanor.

“It’s like a straw forest. It looks like a rock,” says Tabitha.

“It’s going to collapsilate!” Rafael warns. “Guys, stop! Stop—it’s going to collapse. I think one is going to fall, and all the rest are going to fall off ’cause it’s wiggling.”

“Rafael, you’re really thinking about keeping the bowl from collapsing,” I say.

“Yeah,” he replies.

“If you spin so fast, it will wreck,” Mabel adds.

As the children engage with the vessel more carefully, we discuss possible next steps, including making the vessel “hard forever” by cooking it in a really hot oven called a kiln.

“Cook it. Cook it,” says David.

Amy touches the bowl. “This will be really hot.”

I offer a possibility: “Maybe we could put it in a kiln—an oven for clay—to make it hard forever.”

We pause.

“But what about the straws?” someone asks.

“Would they melt?” Mabel wonders.

“Should we try it and see what happens?” Eleanor asks. “We’ve never done it, and I don’t know what would happen.”

“That would be a good way to find out,” I say. “But I’m not sure we could do that here.”

“Daycare doesn’t have an oven,” Amy adds.

“Daycare has a regular oven, but when plastic melts it makes a really stinky smell. I am thinking it may make people sick. I don’t think it is a good idea,” I offer, sharing my worry.

The vessel waits. Ready, maybe. But not without risk.

David leans in.

“Maybe we grab them out. Maybe drag them out.”

David’s idea inspires many children to reach for the straws.

“Don’t put your hand on it!” Tabitha warns. “I saw it move—it can collapse!”

“Is everyone okay if we take the straws out?” I ask.

“Yeah,” the children reply.

“Is anyone worried?” Some nod.

“Why?”

“’Cause it might collapse,” Eleanor says.

“Yeah,” I say, “that’s a risk we’re going to take. It feels strong to me, though.”

“I’m sad. I think it’s going to break,” says Tabitha.

“I’m still worried,” Eleanor adds.

“Some of us think it might break. Some of us don’t,” I say. “But we’ve decided to try—to experiment. Let’s see what happens.”

Many of the children still want to pull out the straws. We talk a bit about how to do that, then start. David is the first to try.

“Is it going to collapse?” Amy asks.

“I don’t think so,” I say.

David grips a straw.

“I think it’s too hard for me!”

“David, you can do it. Be careful,” says Mabel.

One by one, the children pull. A few pieces fall.

“That’s okay. We can fix it,” Mabel says.

Eventually, all the straws are removed. The vessel remains.

I let the children know I’ll take it to the kiln in a week.

“How will you carry it?” Rafael asks.

We pause, remembering. The first bowl had collapsed after being moved too many times. The memory hangs in the air—not as a warning, but as a question: How do we carry something fragile and shared?

Back from the kiln

I brought the vessel back to the centre after it was bisque-fired in a kiln. There was a buzz of comments from the children as they experienced the vessel in its new state.

“It’s so hard.”

“And all white!”

“I like the sound.”

“It is not hot!”

To paint … but how?

When the vessel returned from the kiln, we offered the children brushes and small trays with daubs of paint. The small-tipped brushes were a deliberate choice: their fine tips required careful, slow movements. The children gathered closely around the table, each dipping a brush and finding space along the surface of the vessel.

The painting unfolded without hurry. The small brushes made it difficult to cover large areas quickly, and this seemed to affect how long the children stayed. They didn’t move on quickly. They waited, watched, and added colour in measured strokes. The pace made room for conversations, some quiet, some playful, and some more unexpected.

As they painted, the children talked:

“I made purple,” Amy said.

Grady shared, “I mixed a rainbow! Look.”

Tarik remembered, “My dad has those paints. He painted a dinosaur.”

“I wasn’t feeling good last day,” Alaina sighed.

“Did you put this in the microwave yet?” Mabel asked as she applied paint to the vessel. “Is it a magic microwave?”

“The bowl has been in a really hot oven one time, and we might decide to put it in again.” I responded.

Lydia joined the conversation. “I have window stickers.”

“Me too, to scare the birds.”

“You can get a monster sticker to scare them away!” Landon laughed.

The conversation turned briefly toward birds, windows, and what happens when birds are hurt. These were not planned discussions. They emerged as the children stayed around the vessel. The combination of close physical proximity, the slow work of painting, and the openness of the moment created conditions where children responded to each other. They were not just speaking to the adults or narrating their actions, but listening, adding on, and staying in dialogue with one another.

This painting moment did not aim to finish the vessel or decorate it in a specific way. Instead, it became part of the longer process of being with clay, another way the children gathered, contributed, and stayed present with something shared.

What relationships, conversations, and questions become possible when we resist the urge to rush toward completion?

Working with clay over many months invited us to stay with the slow, layered work of collectivity. Rather than aiming for a finished product, we returned to the same material and the same questions. How do we build something shared? What does it take to stay with each other?

The vessel never belonged to a single child. Its shape changed through contributions, collapses, and quiet negotiations. Its surface held fingerprints, stories, and paint applied in thin, careful strokes. The fine brushes encouraged children to linger and talk. Sometimes they spoke about the bowl, but often they moved toward memories, small observations, and conversations that drifted without needing to resolve.

Clay’s softness and weight asked us to slow down. It held what we added and remembered what came before. These qualities created space for returning, for pausing, and for making decisions together. These encounters unfolded over more than a year and a half. Some lasted only minutes; others stretched across hours, returning again and again to the shared vessel and the questions it carried.

*Children’s names are pseudonyms.

References

[1] Nicole Land, Cristina Delgado Vintimilla, Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, and Lucille Angus, “Propositions Toward Educating Pedagogists: Decentering the Child,” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 23, no. 2 (2022): 109–121.

[2] Early Childhood Pedagogy Network, “Drawing in Pedagogical Practice,” February 8, 2022. https://ecpn.ca/drawing-in-pedagogical-practice/ .

[3] Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, Sylvia Kind, and Laurie L. M. Kocher, Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education, 2nd edn (New York: Routledge), 2024).